Which Gospel Was Written First?

At first glance, the question of which Gospel was written first might seem unimportant. It matters because it is intertwined with the issue of who wrote the Gospels and which Gospels are canonical. In the second century, there were more spurious Gospels afloat than authentic ones. It is the early Christians who decided that only four Gospels were genuine. They also recorded who wrote those Gospels and in what order. None of the Gospel writers identify themselves in the text of their Gospels. It was the early Christians who placed their names as the titles to their works. Those same early Christians uniformly testify that Matthew was the first Gospel written. However, in the nineteenth century, liberal theologians came up with the proposition that Mark wrote his Gospel first and that the person we know as “Matthew” copied Mark. This was intended as an express challenge to the reliability of the early Christian witness. Those theologians were not only questioning the order of the Gospels, but who the real authors were.

So let us briefly examine the historical record. Irenaeus (c. 170) writes,

“Matthew issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, also handed down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, published a Gospel himself during his residence at Ephesus in Asia.”

Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian do not give the entire order of all four Gospels, but they both verify that Matthew was written before Mark. Tertullian also testifies that Mark obtained his information from Peter. A few decades after Tertullian, Origen wrote,

“Concerning the four Gospels that alone are uncontroverted in the Church of God under heaven, I have learned through Tradition that the Gospel according to Matthew was written first. Matthew was at one time a tax collector and afterwards an apostle of Jesus Christ. He composed it in the Hebrew language and published it for the converts from Judaism. The second Gospel written was that according to Mark, who wrote it in accordance with the instruction of Peter, who, in his General Epistle, acknowledged him as a son, saying, ‘The church that is in Babylon, elect together with you, salutes you; and so does Mark my son’ [1Pet. 5:13]. And third, was that according to Luke, the Gospel commended by Paul, which he composed for the converts from the Gentiles. Last of all was the one according to John.”

When Origen speaks of “tradition,” he does not mean hearsay or conjecture. Rather, he means this was the established teaching of the churches of Christ. A century later, the church historian Eusebius wrote,

“Of all of the disciples of the Lord, only Matthew and John have left us written memorials. Tradition says they were led to write only under the pressure of necessity. Matthew, who originally had preached to the Hebrews, when he was about to go to other peoples, committed his Gospel to writing in his native language, and thus compensated those whom he was obliged to leave for the loss of his presence. And when Mark and Luke had already published their Gospels, they say that John, who had employed all his time in proclaiming the Gospel orally, finally proceeded to write his.”

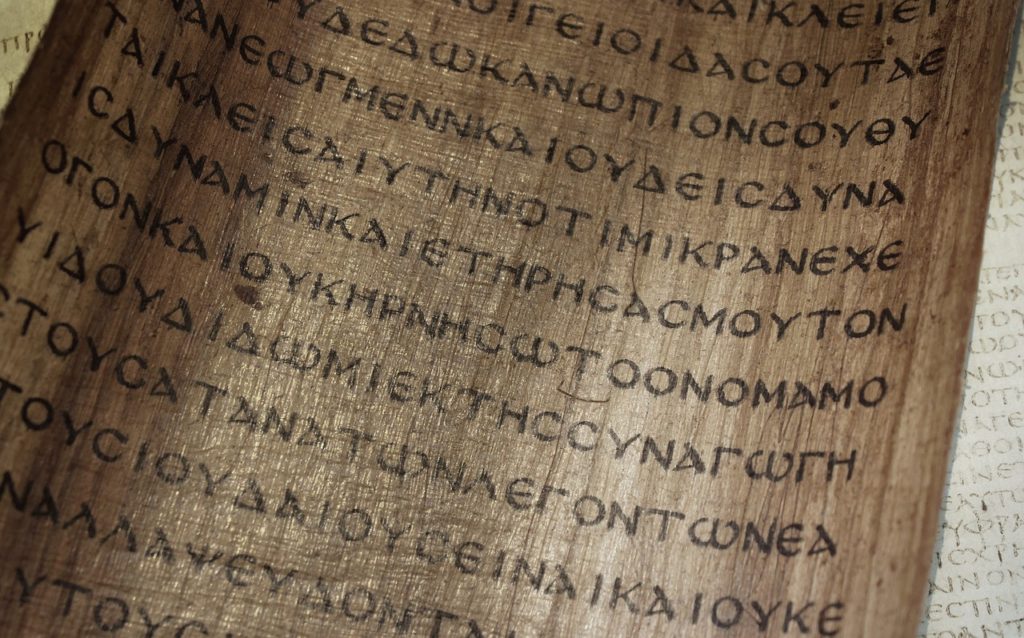

Added to the weight of this testimony is the witness of the ancient New Testament manuscripts. Whether they reflect the Alexandrian textual tradition or the Majority Text, all ancient New Testament manuscripts place the Gospels in the order of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This uniformity is especially significant because the order of the epistles sometimes varies between ancient manuscripts.

The Origin of the Marcan Hypothesis

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, virtually no one questioned the established order of the Gospels. The historical testimony was too strong. However, in the German Lutheran seminaries, liberal theologians scoffed at the notion that the four Gospels were written by the persons to whom the early Christians attributed them. They also openly questioned the historicity of the Gospels. So it is no wonder that these same theologians began to question the order in which the Gospels were written.

In 1838, a German theologian named Christian Gottlob Wilke argued that Mark was the first Gospel written. He said that Matthew and Luke used Mark for their source material. His argument is known today as the Marcan Hypothesis. In itself, it does not matter in which order the four Gospels were written. However, if the writer of the Gospel of Matthew used Mark as the source of his material, it would indicate that it was not really written by the apostle Matthew. After all, Matthew was an eyewitness to the events described, and Mark was not. An eyewitness would not turn to somebody who was not an eyewitness for his source of information. So the Marcan Hypothesis casts doubt on the authorship and reliability of the Gospels. Therefore, it is not surprising that liberal theologians quickly adopted Wilke’s hypothesis. It was not because his arguments were particularly sound or logical. It was because his hypothesis helped to undermine the reliability of Scripture. In fact, a major weakness in Wilke’s hypothesis is obvious to anyone who compares Matthew and Mark. About half of the material in Matthew is not even found in Mark. So how could Mark have been the source of Matthew’s material? Because of this obvious weakness, later theologians invented the existence of an unknown written source that Matthew supposedly used in addition to Mark. This unknown source (or sources) is known today as Q. This designation came from the German word quelle, which means “source.” Before 1900, German theologians were the primary ones promoting the Marcan Hypothesis. However, in the early 1900s, the British theologian, B. H. Streeter introduced this hypothesis to the English-speaking world.

The “Proofs” of the Marcan Hypothesis

B. H. Streeter set forth five basic arguments that supposedly prove the priority of Mark. It is worth examining his arguments, for the same “proofs” are commonly presented today. The arguments below are quoted directly from Streeter.

Streeter’s Proof No. 1: “Matthew reproduces 90% of the subject matter of Mark in nearly identical language with that of Mark; Luke does the same for rather more than half of Mark.”

Here Streeter commits the common fallacy known as begging the question.That is, his “evidence” is merely a restatement of his hypothesis. His hypothesis is that Matthew reproduced his material from Mark. But Streeter’s first argument in no way proves this. Stated objectively, the facts are that 90% of the subject matter of Mark can be found in Matthew. This might suggest that Matthew copied his material from Mark. But it could equally suggest that Mark copied his material from Matthew. For example, let’s suppose that two students both write essays on the life of a famous person. Their teacher finds that 90% of the material in student A’s essay is also included in student B’s essay. This might suggest that student B copied his material from student A. Yet, it would equally suggest that student A might have copied his material from student B. And, of course, there could be other explanations for the situation. In the case of Matthew and Mark, there is further evidence that must be taken into account. Nearly half of the subject matter of Matthew is not found in Mark. So if there were any copying, it would appear to be virtually certain that it was Mark who copied Matthew and not the other way around. Nevertheless, there are still further facts to weigh. It may be that 90% of the subject matter of Mark can be found in Matthew. However, when describing each event in Jesus’ life, Mark provides additional details not found in Matthew. So even if Mark used Matthew as one of his sources, he evidently had an additional source for his information. In the end, the facts perfectly fit the historical testimony of the early Christians. Matthew wrote his Gospel first. He was an eyewitness to most of the events about which he wrote. He needed no other human source. Mark was not an eyewitness, so he had to depend upon others. He may have had access to Matthew’s gospel when he wrote. However, he obviously had another eyewitness source, whom the early Christians identify as Peter.

Streeter’s Proof No. 2: “In any average section which occurs in all three Gospels, the majority of the actual words used by Mark are reproduced by Matthew and Luke, either alternately or both together.”

Streeter’s second argument is almost identical to his first, except that he talks about “words” instead of “subject matter.” And once again he commits the fallacy of begging the question. He asserts that Matthew and Luke “reproduce” the words of Mark, but he offers no evidence that they have done so. His evidence is merely that the three synoptic evangelists use most of the same words when they describe the same events.

That might suggest there was borrowing among them, but it in no way indicates who borrowed from whom. It certainly does not disprove that Matthew wrote his Gospel first. Furthermore, the usage of the same words by the three evangelists is not as unusual as it may seem at first glance. That is because the entire New Testament uses less than 5450 different Greek words. So when the Gospel writers narrate the same events, we would expect them to largely use the same words.

Streeter’s Proof No. 3: “In general, the relative order of incidents and sections in Mark is supported by both Matthew and Luke. Where either of them deserts Mark, the other is usually found supporting him. This conjunction and alternation of Matthew and Luke in their agreement with Mark as regards to (a) content, (b) wording, and (c) order is only explicable if they are incorporating a source identical, or all but identical, with Mark.”

Once again, Streeter “begs the question” by assuming his conclusion within his argument. If his underlying information is accurate, all he is stating is that “the relative order of incidents” in Matthew, Mark, and Luke are the same. This merely suggests that these three evangelists roughly followed a chronological order in their narrations of events. Streeter’s facts could just as easily be used to argue the priority of Matthew. Streeter also asserts that when Matthew and Luke do not agree on the order of events, one or the other usually agree with Mark. Another way to state the same phenomenon is that Mark’s order of events usually agrees with either Matthew or Luke. None of this contradicts the historical position. It suggests that Mark followed Matthew’s sequence most of the time. However, at times Mark chose to relate events in a different order, probably based on information from Peter. When Mark chose not to follow Matthew’s sequence, Luke usually followed Mark’s sequence rather than Matthew’s.

Streeter’s Proof No. 4: “The primitive character of Mark is further shown by (a) the use of phrases likely to cause offense, which are omitted or toned down in the other Gospels and the (b) roughness of style and grammar and the preservation of Aramaic words.”

Here, Streeter takes a different tack. However, this argument is as weak as his others because it is highly subjective. Streeter picks and chooses what he calls “phrases likely to cause offense.” For example, he compares Mark 3:10 and Matthew 12:15. Mark writes, “He healed many, so that as many as had afflictions pressed about Him to touch Him.” Matthew describes the same episode in these words: “He withdrew from there, and great multitudes followed him, and he healed them all.” According to supporters of the Marcan Hypothesis, Matthew was copying Mark, but he tried to make Jesus look better by changing “he healed many” to “he healed them all.” However, to describe Mark’s account as one “likely to cause offense,” is highly imaginative. In fact, it is unlikely that any Christian has ever found it offensive. Both evangelists say the same thing, but use a different choice of words. This is actually a strong argument that neither copied from the other. In reality, Mark is being more precise than Matthew. Not everyone needed physical healing. So technically, Jesus healed “many,” not “all.” When Matthew says that Jesus healed “them all,” he obviously meant Jesus healed all who were sick. Jesus did not heal healthy people. Other supposed examples of Mark using “offensive language” are the following verses: “He looked upon them with anger, being grieved at the hardness of their hearts” (Mk. 3:5). “And when his friends heard of it, they went out to lay hold on him, for they said, ‘He is beside himself’” (Mk. 3:21). “But when Jesus saw it, he was very displeased [with his disciples]” (Mk. 10:14). None of those statements appear in Matthew or Luke. Supposedly, Matthew and Luke took them out of their Gospels in order not to cause offense. But that is pure conjecture. In fact, examples of “offensive passages” can be found in Matthew and Luke that are omitted in Mark. For example, Matthew alone includes the extended denunciation of the scribes and Pharisees found in Matthew 23. If the number and length of “offensive passages” indicate which Gospel was written first, a strong argument could be made for the priority of Matthew on that basis alone. Of course, in reality the matter of “offensive language” is a subjective, conjectural argument that proves nothing.

The same can be said of Streeter’s argument that Mark uses more Aramaic words than Matthew. Somehow, this is supposed to make Mark’s Gospel more “primitive” and therefore earlier in time. However, the truth of the matter is that Mark uses eight Aramaic words, and Matthew uses five. Neither evangelist uses many Aramaic words, and the difference between the two is insignificant.

Streeter’s Proof No. 5: “The way in which Marcan and non-Marcan material is distributed in Matthew and Luke respectively looks as if each had before him the Marcan material in a single document, and he was faced with the problem of combining this with material from other sources.”

This is the weakest of Streeter’s shaky arguments, for it is nothing more than a restatement of his hypothesis in different words. Streeter began with the conclusion that Matthew and Luke used Mark and Q as the sources of their Gospels. So to Streeter it looks as though Matthew and Luke each had Marcan material and Q material in front of them in compiling their Gospels. However, the same facts look quite different to someone who holds to the historical model.

In summary, all of Streeter’s arguments are either fallacious or highly subjective. His arguments can hardly overturn the consistent testimony of the early Christians that Matthew was the first Gospel written. The Marcan Hypothesis epitomizes Paul’s words about unbelievers: “Although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God, nor were thankful, but became futile in their thoughts, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools” (Rom. 1:21-22 NKJV).

Conservative Theologians and Commentators

Surprisingly, many conservative theologians and commentators have embraced the Marcan Hypothesis. The reason for this is obviously not the weight of the arguments put forth to support that hypothesis. Indeed, those arguments are flimsy. Rather, conservative scholars have adopted the Marcan Hypothesis because of the herd mentality among scholars. Although scholars like to think of themselves as independently minded, most of them uncritically follow whatever is currently in vogue in academic circles. They do not want to be labeled as unscholarly or “behind the times.” However, they are unwittingly falling into the trap of dismissing the historic testimony of the early church. If we cannot trust the early Christians’ testimony on the order of the Gospels, why should we trust their testimony as to who wrote the Gospels?

This blog was adapted from David Bercot’s Commentary on Matthew. For citations, see page 490 in Bercot’s commentary.